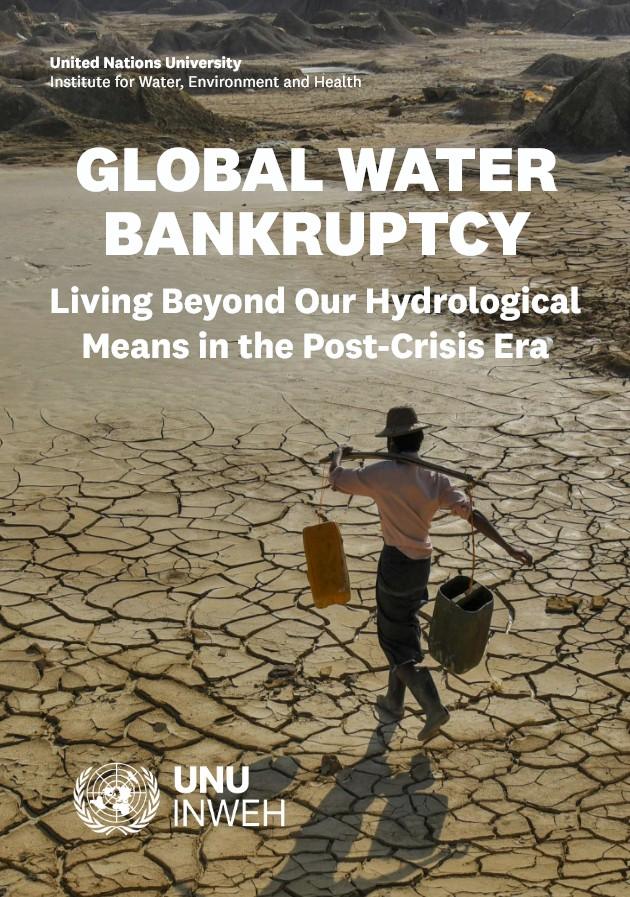

In its flagship report published on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of UNU-INWEH and ahead of the 2026 UN Water Conference, the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health introduces the concept of “global water bankruptcy” to describe a new phase in humanity’s relationship with freshwater resources. The report argues that in many river basins, aquifers, and ecosystems, water stress and recurring crises have given way to a persistent post-crisis condition in which long-term water use exceeds renewable inflows and safe depletion limits, making a return to historical baselines impossible.

Drawing on global evidence, the report documents how climate change, groundwater depletion, over-allocation, declining water quality, and the rapid loss of glaciers and snowpacks are jointly eroding the natural capital that underpins water security. Mountain glaciers and seasonal snowpacks—often described as the world’s “water towers”—are shrinking rapidly, undermining dry-season water supplies for billions of people and destabilizing agriculture, hydropower, and ecosystems downstream. At the same time, agriculture, which accounts for more than 70 percent of global freshwater withdrawals, is increasingly exposed to chronic scarcity, with severe implications for food security, livelihoods, and migration, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

The report emphasizes that today’s water shortages are increasingly anthropogenic in nature. Persistent over-extraction, land degradation, pollution, and disrupted hydrological cycles now play a greater role than short-term climatic variability in shaping drought severity and duration in many regions. Urban “Day Zero” events—when cities come close to running out of piped water—are presented as the urban manifestation of this structural overshoot rather than isolated emergencies.

Against this backdrop, Global Water Bankruptcy calls for a fundamental shift in the global water agenda: away from repeated crisis response and towards bankruptcy-aware water governance. This approach focuses on preventing further irreversible damage, protecting remaining water-related natural capital, rebalancing rights and expectations, transforming water-intensive development models, and explicitly safeguarding vulnerable communities. Framed not only as a growing risk but also as a potential platform for cooperation, the report argues that serious investment in water can generate co-benefits across climate action, biodiversity protection, food systems, and peacebuilding, and help rebuild trust in an increasingly fragmented world.

Links:

- UNU-INWEH Report: Madani, K. (2026): Global Water Bankruptcy: Living Beyond Our Hydrological Means in the Post-Crisis Era, United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health (UNU-INWEH), Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada.

doi: 10.53328/INR26KAM001 - Madani, K. (2026): Water Bankruptcy: The Formal Definition. Water Resources Management Volume 40, article number 78. doi: 10.1007/s11269-025-04484-0

- UNU-INWEH – United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health

- Press release, UN Headquarters, New York (20 January 2026)

- Official Webpage of the United Nations Water Conference United Arab Emirates, 2026